Water-Borne Diseases: Cholera and Dysentery: Cholera: Scourge of the Poor

Cholera: Scourge of the Poor

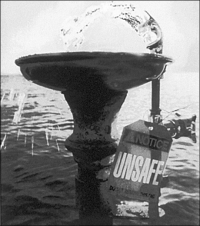

Drinking water can be contaminated during natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes. (Courtesy CDC)

Cholera is not a problem in developed countries, but it is a major public health problem for developing countries, where outbreaks occur seasonally and are associated with poverty and poor sanitation. The disease causes profuse watery diarrhea that leads to rapid dehydration and—if not treated—death. Serious disasters, such as hurricanes, typhoons, or earthquakes, cause a disruption in water systems resulting in the mixing of drinking and waste waters, which increase the risk of contracting cholera among area residents.

Compared to diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis, which have been around for thousands of years, cholera is a relatively new disease. Its origins can be traced to India in 1826, but by 1830, 40,000 people a year were dying from cholera. In 1831, nearly 200,000 Russians died. The same year, cholera spread to Poland, Hungary, and Germany, killing hundreds of thousands. As it spread throughout Europe, the death toll rose dramatically. In 1848, Russia alone suffered 3 million deaths! Large outbreaks continued for many decades, killing hundreds of thousands of Europeans each year.

Infectious Knowledge

His obsession was the dangerous lack of sanitation in the city. He appealed to the highest authorities to fill in the Spanish sewers that were immense breeding grounds for rats, and to build in their place a closed sewage system whose contents would not empty into the cove at the market, as has always been the case, but into some distant drainage area instead. The well-equipped colonial houses had latrines with septic tanks, but two thirds of the population lived in shanties at the edge of the swamps and relieved themselves in the open air. The excrement dried in the sun, turned to dust, and was inhaled by everyone along with the joys of Christmas in the cool, gentle breezes of December … He was aware of the mortal threat of the drinking water.

—Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

Cholera spread throughout the world in seven large pandemics. The seventh pandemic began in 1961 in Indonesia and subsequently affected approximately 100 more countries. In some areas, more than 20 percent of the people got sick and often half of them died because medical treatment was not available. The pandemic reached Africa in 1970 and moved rapidly throughout the region. By the end of 1971, 25 African countries were reporting cholera outbreaks. Between 3,000 and 43,000 cholera cases were reported in Africa every year until 1990. The following year, a large epidemic affected 14 countries and resulted in more than 100,000 cases and 10,000 deaths.

Cholera's Causes

Cholera is caused by a bacterium that has two specific toxins, or poisons. One causes profuse diarrhea, and the other assists the bacteria in living and multiplying in the intestines.

Most people infected develop mild cases or do not get sick at all, although the bacteria may live in their gut for 7 to 14 days. The vast majority of people who get cholera are cured when rapid treatment is available. However, without treatment, death rates are between 50 and 70 percent.

Antigen Alert

The disease-causing genes in the bacterium that causes cholera are on one particular chromosome, or portion of the bacteria's DNA. Sometimes these genes are transferred from the bacteria to other organisms. When this happens, the organism that receives the piece of DNA from the cholera-causing bacteria goes on to cause disease.

A variety of bacteria exchange genes this way. It can happen through direct physical contact between organisms, uptake of free DNA, or when certain viruses, called bacteriophages, carry genetic material from one organism to another.

In addition to making some bacteria virulent, genetic transfer can also help spread drug resistance genes from one organism to another.

Don't Drink the Water

Cholera is a diarrheal disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It is almost always transmitted by water or food that has been contaminated by human waste. Surface water and water from shallow wells are common sources of infection, where bathing or washing cooking utensils in contaminated water can also transmit cholera. Foods such as cooked grains that are allowed to sit at or above room temperature for several hours can also be an excellent breeding environment. Raw or undercooked shellfish and raw fruits and vegetables can also transmit the bacterium.

People with infections but no symptoms can carry the disease from place to place causing it to spread, although person-to-person contact is not a significant mode of transmission.

Corralling Cholera

Positive diagnosis of cholera requires identification of the bacteria from stool specimens. Fortunately, cholera can be successfully treated by rapid oral or intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement. Antibiotic therapy can shorten the duration of the disease but does not affect the severity of an attack.

Areas without a safe water supply and good sanitation are at most risk for epidemic cholera. The key to preventing its spread is limiting the growth and survival of the organism that causes it. Outbreaks can be minimized by educating the public about food and water safety, the importance of hand-washing, and the need to use toilets. When an epidemic of cholera occurs, however, total cases and deaths can be reduced by early detection and rapid initiation of treatment and control methods. Cholera epidemics are unpredictable and may recur in either the rainy or dry season. Fortunately, immunity gained from having an infection before protects a person against cholera reinfection.

Potent Fact

The cholera bacterium grows poorly in an acidic environment, so people taking antacids or other products to reduce stomach acid are more susceptible.

Protecting Against Cholera

The only cholera vaccine available now gives partial protection for only three to six months—it does not provide long-term protection like other vaccines. For that reason, it is not recommended to prevent or control cholera outbreaks because it may give a false sense of security to those vaccinated and to public health authorities, who may then forgo implementing more effective measures.

There are two oral vaccines with few side effects that are given outside the United States. These vaccines provide 60 to 100 percent protection against major outbreak strains for at least six months.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Dangerous Diseases and Epidemics © 2002 by David Perlin, Ph.D., and Ann Cohen. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.