The Supreme Court: Oliver Wendell Holmes (1902-1932)

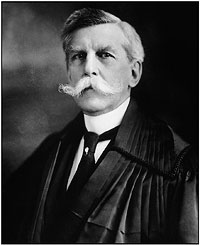

Oliver Wendell Holmes (1902-1932)

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Oliver Wendell Holmes to the United States Supreme Court in 1902. Prior to that time, Holmes served as a Massachusetts Supreme Court judge and taught at Harvard College. Holmes also served on the Twentieth Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War and was wounded three times.

He received his degree from Harvard Law School in 1867, but his law practice was never very successful. He gained his fame when he was invited to give a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute, which were published in a book called The Common Law in 1881. The Lowell Institute was established in Boston in 1836 to bring distinguished lecturers to the city.

Holmes was known for both his intellect and humor. He strongly believed in the principle that law was built on experiences and not logic. He believed it was important to look at the facts of a changing society rather than to cling to old slogans and formulas. Holmes worked to convince people that the law should develop along with the society it serves. He also championed the idea of “judicial restraint” because he believed judges should avoid letting their personal opinions impact their decisions.

Photograph of Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes by Harris and Ewing.(From the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

Supreme Sayings

“The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, institutions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation's development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics.”

—From the first of 12 Lowell Lectures delivered by Oliver Wendell Holmes on November 23, 1880

Lochner v. New York

Some of Holmes' most famous writings as a Supreme Court Justice are pulled from his dissents on landmark cases. Two of those we discussed in the preceding section.

The first is Lochner v. New York. In that case the Supreme Court overturned a New York law that mandated maximum work hours for bakers. Holmes dissented on that decision and said:

- “This case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain. If it were a question whether I agreed with that theory, I should desire to study it further and long before making up my mind. But I do not conceive that to be my duty, because I strongly believe that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a majority to embody their opinions in law. … But a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the State or of laissez faire. It is made for people of fundamentally differing views, and the accident of our finding certain opinions natural and familiar or novel and even shocking ought not to conclude our judgment upon the question whether statutes embodying them conflict with the Constitution of the United States.”

Adkins v. Children's Hospital

The second case (discussed in the previous section) also involved legislation that tried to mandate working conditions, Adkins v. Children's Hospital. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not establish minimum wage rates. Holmes disagreed and wrote this in his dissent:

- “The question in this case is the broad one, whether Congress can establish minimum rates of wages for women in the District of Columbia with due provision for special circumstances, or whether we must say that Congress has no power to meddle with the matter at all. To me, notwithstanding the deference due to the prevailing judgment of the Court, the power of Congress seems absolutely free from doubt. The end, to remove conditions leading to ill health, immorality and the deterioration of the race, no one would deny to be within the scope of constitutional legislation. The means are means that have the approval of Congress, of many States, and of those governments from which we have learned our greatest lessons. When so many intelligent persons, who have studied the matter more than any of us can, have thought that the means are effective and are worth the price, it seems to me impossible to deny that the belief reasonably may be held by reasonable men. If the law encountered no other objection than that the means bore no relation to the end or that they cost too much, I do not suppose that anyone would venture to say that it was bad. I agree, of course, that a law answering the foregoing requirements might be invalidated by specific provisions of the Constitution. For instance, it might take private property without just compensation. But in the present instance, the only objection that can be urged is found within the vague contours of the Fifth Amendment, prohibiting the depriving any person of liberty or property without due process of law.”

Abrams v. United States

Another famous Holmes dissent was in the case of Abrams v. United States in 1923. This case involved the publishing of two political publications during World War I that supported the Germans.

Just the Facts

All five of the defendants in Abrams v. United States were born in Russia. They lived in the United States for 5 to 10 years, but none had applied for citizenship. Four of the defendants admitted they were rebels, revolutionists, and anarchists who did not believe in government in any form. One did testify that he believed in a socialist government, but not a capitalist government like that of the United States.

The Supreme Court held that these publications were unlawful on the basis that the information was:

- “disloyal, scurrilous and abusive language about the form of Government of the United States,”

- “intended to bring the form of Government of the United States into contempt, scorn, contumely and disrepute;”

- “intended to incite, provoke and encourage resistance to the United States in said war.”

This time his dissent was signed by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who we'll discuss next. They often dissented jointly while on the court together. Holmes said:

- “But, as against dangers peculiar to war, as against others, the principle of the right to free speech is always the same. It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned. Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Now nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government arms or have any appreciable tendency to do so. Publishing those opinions for the very purpose of obstructing, however, might indicate a greater danger, and, at any rate, would have the quality of an attempt. …

- “In this case, sentences of twenty years' imprisonment have been imposed for the publishing of two leaflets that I believe the defendants had as much right to publish as the Government has to publish the Constitution of the United States now vainly invoked by them. … It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.”

Buck v. Bell

Holmes was also known for facing some darker moments. One of his worst decisions was Buck v. Bell in 1927. This case involved the right of the state of Virginia to sterilize a “feeble-minded white woman“ against her will. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of allowing the sterilization. Holmes wrote the Court's opinion and said:

- “We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped by incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for a crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

This ruling did not sit long on the books. The first move to overturn was in 1942 in the case Skinner v. Oklahoma, which involved an Oklahoma law that allowed forced sterilization of habitual criminals. Skinner was an armed robber and chicken thief. The Supreme Court decided in favor of Skinner, ruling that procreation was a “fundamental right of man” and that forcible sterilization violated Skinner's Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Holmes resigned from the court in January 1932 after serving for 29 years. He left the court at the age of 90 and died three years later in March 1935 just four days before his 94th birthday.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to The Supreme Court © 2004 by Lita Epstein, J.D.. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.